Penticton Art Gallery, Penticton, B.C. July 5th-September 15, 2019

I have the great pleasure of having an exhibition at the Penticton Art Gallery with my friend and fellow bee-enthusiast-entomologist, Lincoln Best.

Botanical images, graphite drawing of lomatium, and “Summer” display of bees and herbarium specimens.

The title of the exhibition, “Pretty:useful”, hints at the language that we use to talk about plants, and I ask how that use of language reflects our relationship to the plants themselves?

Beautiful, useful, native, exotic, introduced, edible, nutritious, medicinal, noxious, aggressive, lucrative, rare, productive, keystone, endemic, passive, decorative, weedy, extirpated, healing, messy, restored, ornamental…

I question our relationship to plants, and wonder if we can move beyond seeing them as objects for our own use, to a less privileged, less-human-centered perspective to one where we can appreciate plants for themselves, with no question of value or worth to us? As Robert Harrison writes in his book, Gardens. An Essay on the Human Condition:

We historically have lived as if the earth was given for us

…a privileged environment…with no sense of responsibilities towards its care. We saw ourselves as consumers and receivers.

Yarrow, Twin Flower and a Larkspur seed sit next to Small-Flowered Blue Eyed Mary rendered in graphite

Two interconnected projects are presented in this exhibition– a large-scale installation of photographic images of closely observed native flora, printed on paper and dipped in melted beeswax.

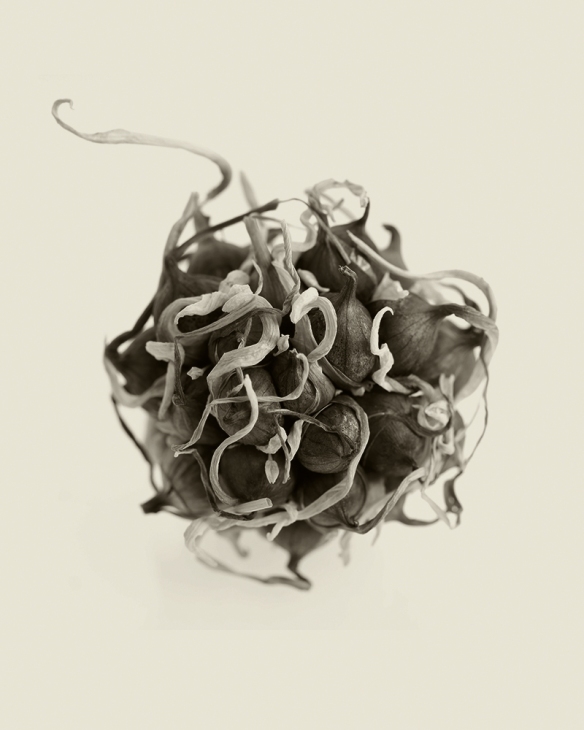

Walking onion. Archival inkjet print, melted beeswax

And as a counterpoint, over 200 little pollen colour drawings, rendered in powdery, soft pastel.

A wall of pollen

Details of Pollen samples

To this, taxonomist Lincoln Best, adds a third thread, a selection of entomological specimens, collected from the myriad diversity of native bees that inhabit this unique region of our province, the southern interior.

Lincoln Best’s “Spring”: herbarium specimens and bees from the early season.

The exquisitely mounted native bees, the pollen studies and the botanical images, represent a mere fragment of the diversity of the native flora and fauna found in the Southern Okanagan Valley, but scientist and artist hope that this limited representation will inspire viewers to explore the wonders to be found in our beautiful, but diminishing natural environments.