Here’s a little study of a beautiful wildflower of the Garry Oak Meadows — Erythranthe guttata, Yellow Monkey Flower. Phrymaceae.

The most dramatic part of this flower, (apart from the golden colour) are the deep crimson markings on the lower petals of the blossom, markings that lead an insect visitor to the nectar. Now, bees see things differently from us, so to see how a bee sees those markings would require both a UV filter and bee-vision filters. An interesting aspect to pursue!

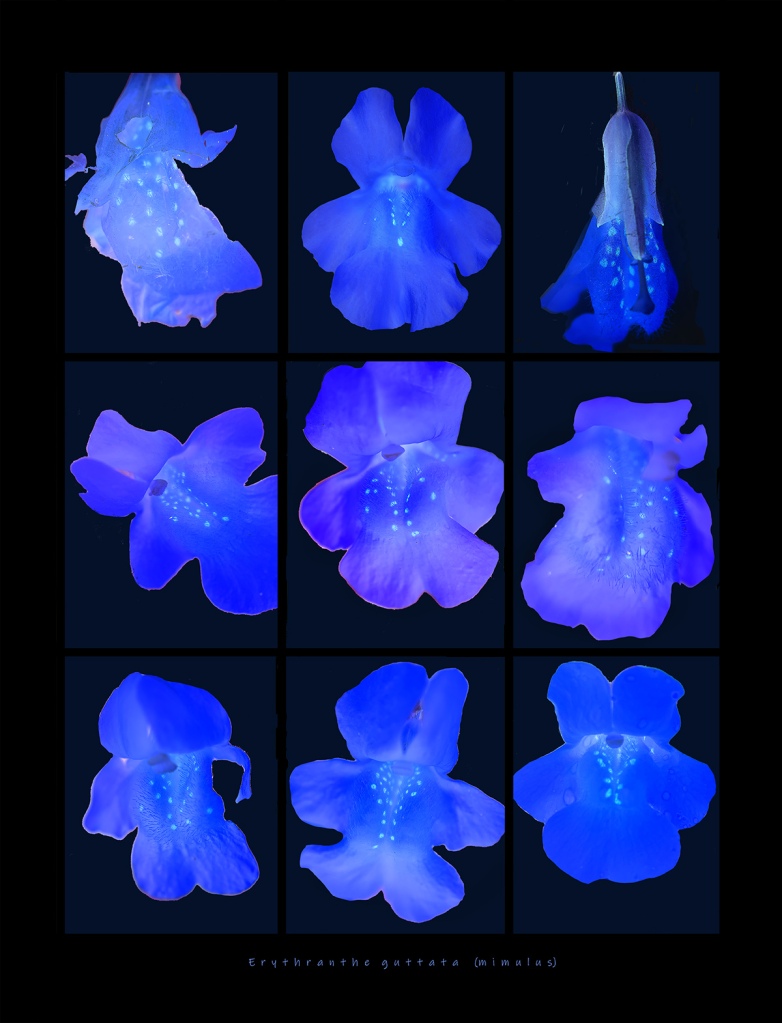

One of the cool discoveries I made in observing the blossoms of this plant is that those markings differ from flower to flower. Here’s a small sample of some of the variations. I’ve morphed the colours in order to enhance the visibility of those markings.

I’ve dissected several blossoms, and another very cool aspect of these blossoms are the very hairy bulges on lower petals. Apparently, the hairs collect not only pollen from the flower’s own anthers — ergo, the plant can self-pollinate, but also pollen carried by incoming bees, so there’s cross-pollination too. Double reproductive security for this plant.

More surprises from this beautiful wildflower — the calyx, the little structure that holds the blossom and all its reproductive parts, inflates after the flower has finished its display, enclosing and protecting the seed pod within its papery cover. I’ve made a short animation to explore this wonderous aspect of the flower’s life cycle. It’s entitled Postcript because it’s the last part of the flower’s life cycle.